Folded 1 2006

National Gallery of Australia, Australian Capital Territory, Australia

Bronze

105 H x 71 W x 54 D cm (41.3 x 28 x 21″)

Monthly Archives: September 2012

From Hope to Optimism

From Hope to Optimism 2011

Rassegna Internazionale di Scultura di Roma Villa Borghese Gardens, Rome, Italy

Bronze and Stainless Steel

3.5 H x 2.5 W x 2.0 D m (11.5 x 8.2 x 6.6′)

From Hope to Optimism 2010

Sculpture by the Sea Bondi 2010, New South Wales, Australia

Bronze and Stainless Steel

3.5 H x 2.5 W x 2.5 D m (11.5 x 8.2 x 8.2′)

From Hope to Optimism 2015

Yabby Lake Vineyard, Moorooduc, Victoria, Australia

Bronze and Stainless Steel

3.5 H x 2.5 W x 2.5 D m (11.5 x 8.2 x 8.2′)

Mother Earth 3

Mother Earth 3 2002

National Gallery of Victoria, Victoria, Australia

Bronze

82 H x 37 W x 34 D cm (32.3 x 14.6 x 13.4″)

Mother Earth 3 2002

Deakin University, Victoria, Australia

Bronze and Stone

30 H x 15 W x 13 D cm (11.8 x 5.9 x 5.1″)

Coil

Coil 1999

Hall Vineyard, CA, USA; Montalto Vineyard, Vic, Australia; Hall Park, TX, USA

Silicon Bronze

3.3 H x 2.4 W x 2.4 D m (10.8 x 7.9 x 7.9′)

Coil 1999

National Gallery of Australia, Australian Capital Territory, Australia

Silicon Bronze

39 H x 31 W x 33 D cm (15.4 x 12.2 x 13″)

Growth

Growth 1999

Mount Scopus College, Burwood, Victoria, Australia

Silicon Bronze

4.3 H x 3.0 W x 2.6 D m (14.1 x 9.8 x 8.5′)

Growth 1999

Hall Office Park, Texas, USA

Silicon Bronze

4.0 H x 2.3 W x 2.0 D m (13.1 x 7.6 x 6.6′)

Growth 1999

Geelong Gallery, Victoria, Australia

Silicon Bronze

40 H x 23 W x 22 D cm (15.8 x 9.1 x 8.7″)

Growing

1996

The largest edition of Growing is 4.3m (169″) in height. One is located at Hall Office Park, Frisco, Texas, USA, the other is in a private collection on the Mornington Peninsula, Victoria, Australia. The maquette is in the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Australia.

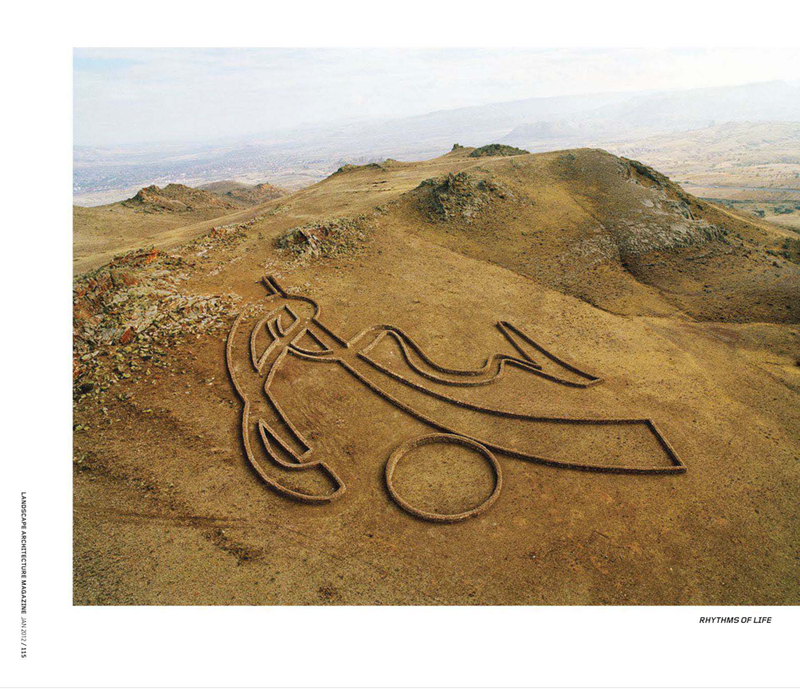

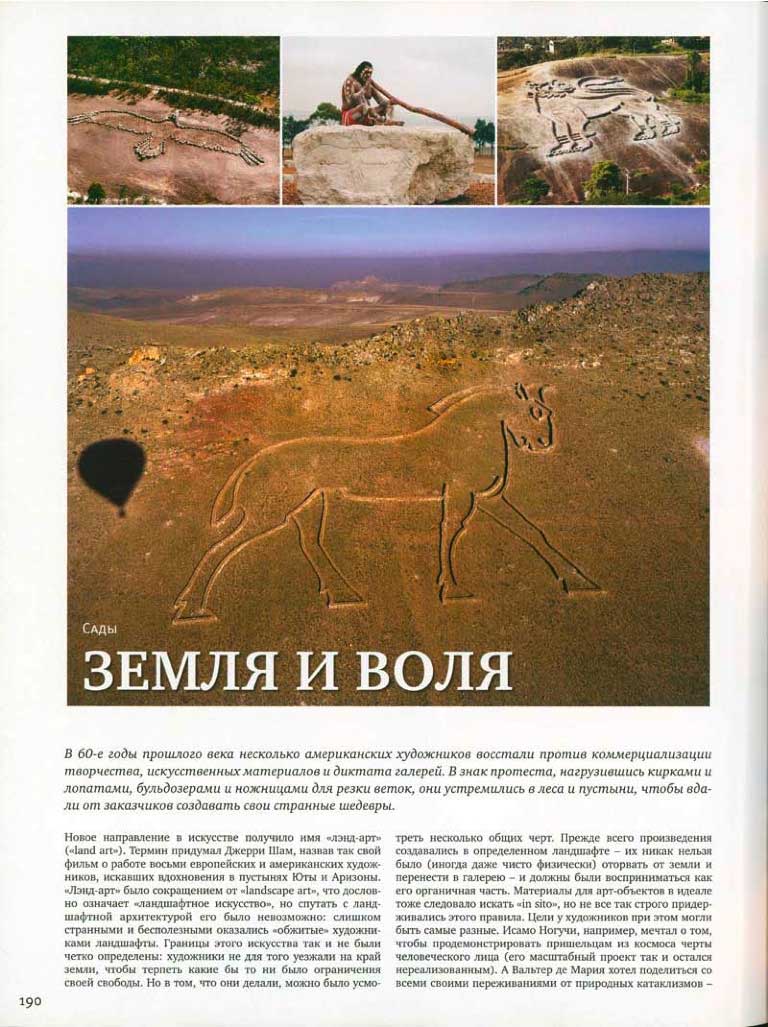

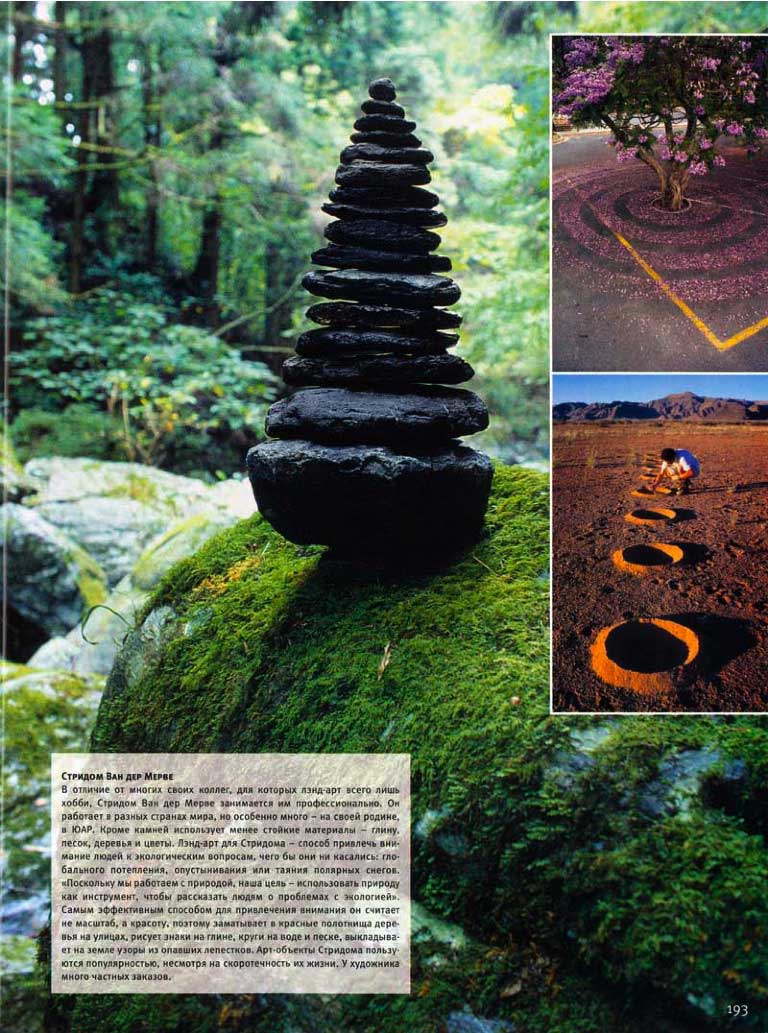

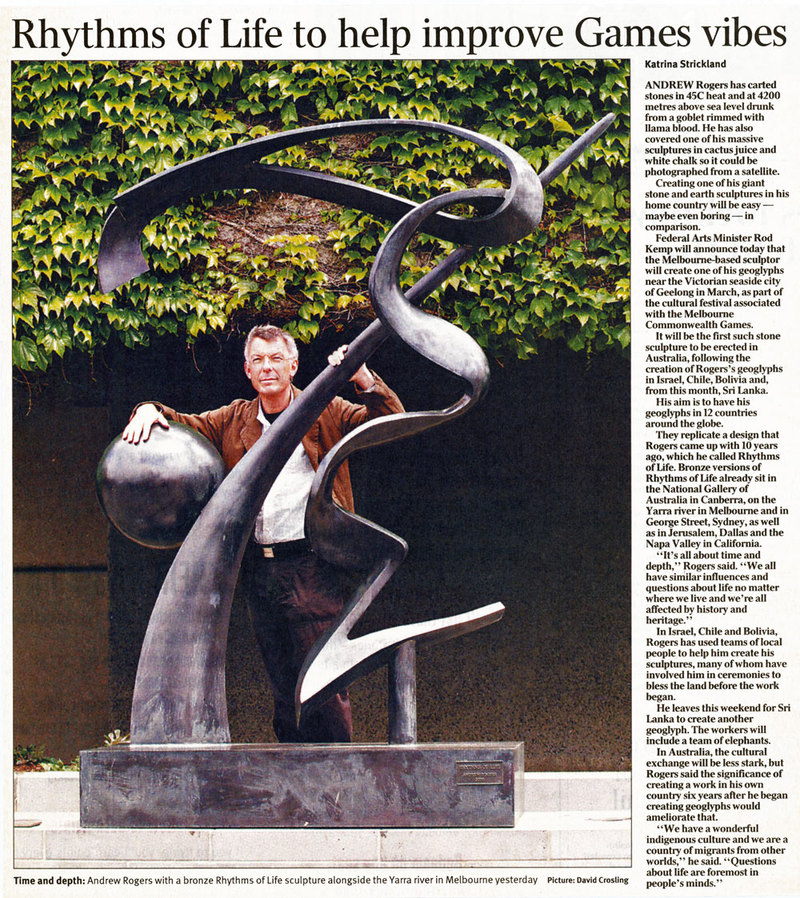

Rhythms of Life

1996

Bronze

The Rhythms of Life bronze sculpture was a catalyst for Andrew Roger’s global Rhythms of Life land art project.

Pillars of Witness

1999

Holocaust Centre

Elsternwick, Victoria, Australia

Bronze

Gates

2007

Red Hill, Victoria, Australia

Bronze

400 H x 360 W cm

(158″ x 142″)

Harmony

1996

Melbourne, Australia

Bronze

W 66 cm

Peak

1996

Melbourne, Australia

Bronze

H 64cm

Heritage

1996

Melbourne, Australia

Bronze

H 66cm

Flora Exemplar

1996

Bronze

Flora Exemplar is located in significant public and private collections around the world. Grounds for Sculpture in New Jersey, USA has a 4.6m (181″) high edition in their collection. A 3.1m (122″) high edition is located in the City of Vienna, Austria. The Art Gallery of New South Wales features a 2.6m (102″) edition in their gardens. The maquette is in the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Australia.

Catching Wind

1996

Bronze

Breaking Out

1997

Dallas, Texas, USA

Bronze

3m

Spirit

1997

Bronze

California, USA, 3m (118″) high & Victoria, Australia 60cm (24″) high.

The maquette of Spirit is in the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Australia, in Canberra.

Balance

1997

California, USA

Bronze

H 2.7m

Evolving

1996

Dallas, Texas, USA

Bronze

H 2.4m

Leading

1997

Elgee Park, Mornington Peninsula, Victoria Australia

Bronze

H 2m

Observe

1997

McClelland Sculpture Park, Langwarrin, Victoria, Australia

Bronze

H 2.6m

Macrocosm

1996

Dallas, Texas, USA

Bronze

H 3m

Rhythms of the Metropolis

1996

Bronze

Large scale editions of Rhythms of the Metropolis up to 6m (20ft) in height are located in Texas, USA; Jerusalem, Israel and the City of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. The maquette is in the permanent collection of the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, ACT.

Evolution

Evolution 1999

Hall Vineyard, California, USA

Silicon Bronze

4.0 H x 3.8 W x 3.7 D m (13.1 x 12.5 x 12.1′)

Evolution 1999

National Gallery of Australia, Australian Capital Territory, Australia

Silicon Bronze

38 H x 48 W x 27 D cm (15 x 19 x 10.6″)

Circles in Bolivia Video

Circles in Bolivia

A brief video about the creation of Andrew Rogers’ Circles geoglyphs in the Altiplano near the Cerro Rico Mountains of Bolivia.

In Bolivia, there are three stone geoglyphs reaching an altitude of 4,360 meters. They are located six kilometres apart and are visible from one another due to the clear atmosphere at this altitude.

These geoglyphs were constructed with the help of 800 workers, most in traditional dress.

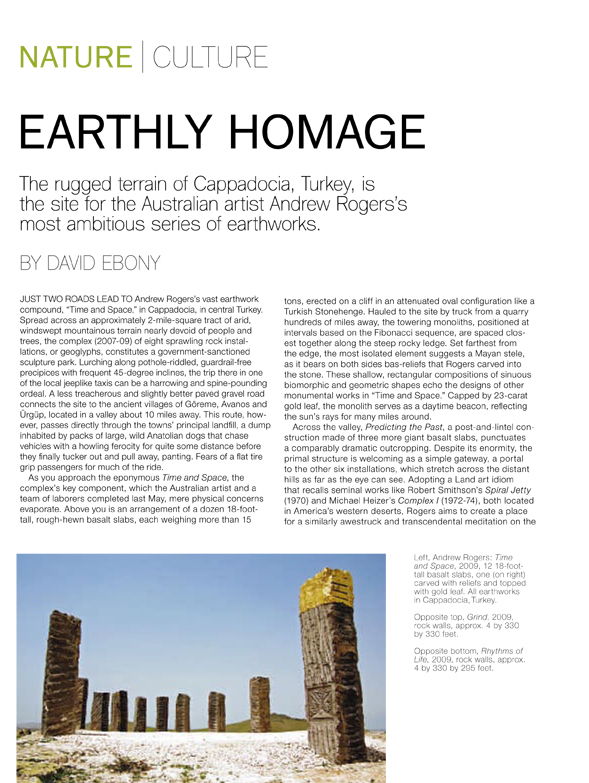

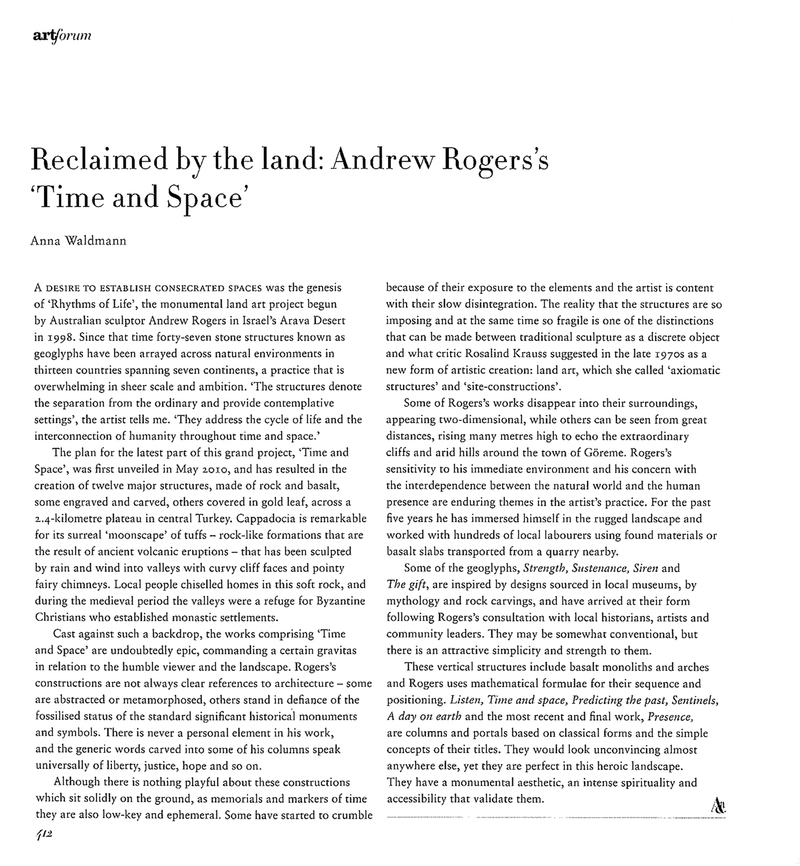

Sculpture March 2012

Art & Australia March 2012

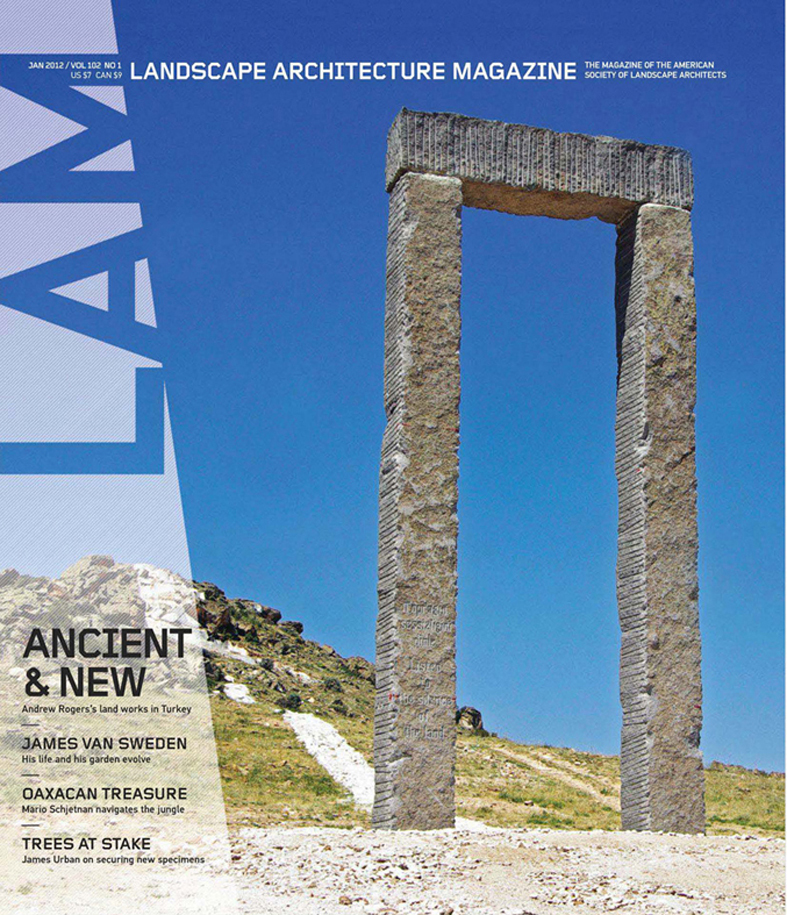

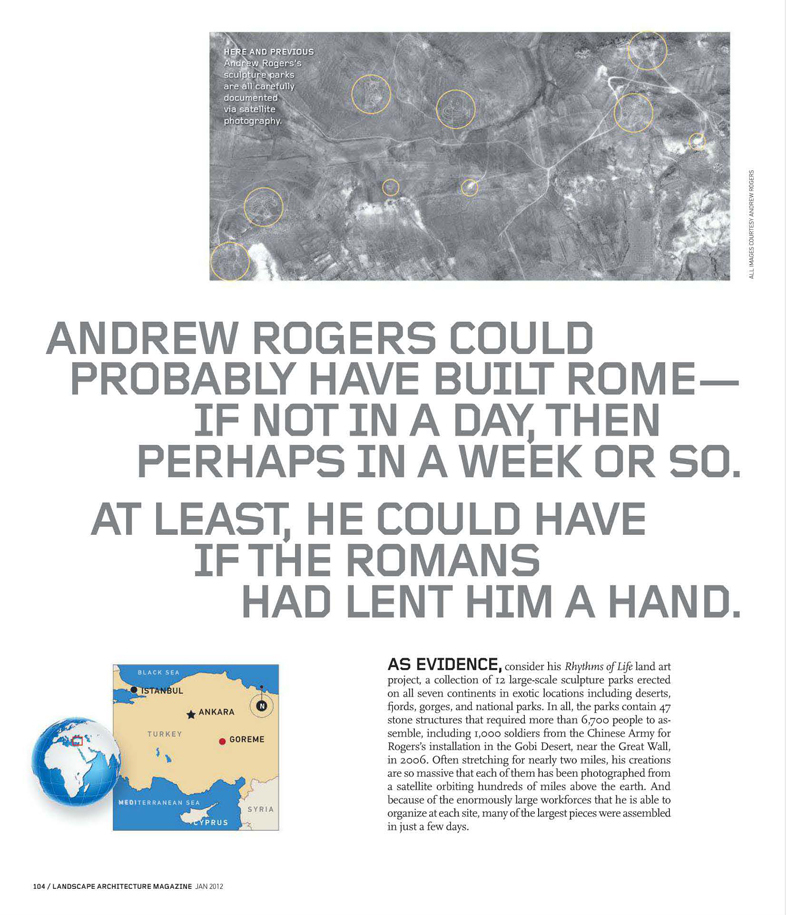

Landscape Architecture Magazine Jan 2012

“Andrew Rogers could probably have built Rome – if not in a day, then perhaps in a week or so.

At least, he could have if the Romans had lent him a hand.”

James Grayson Trulove

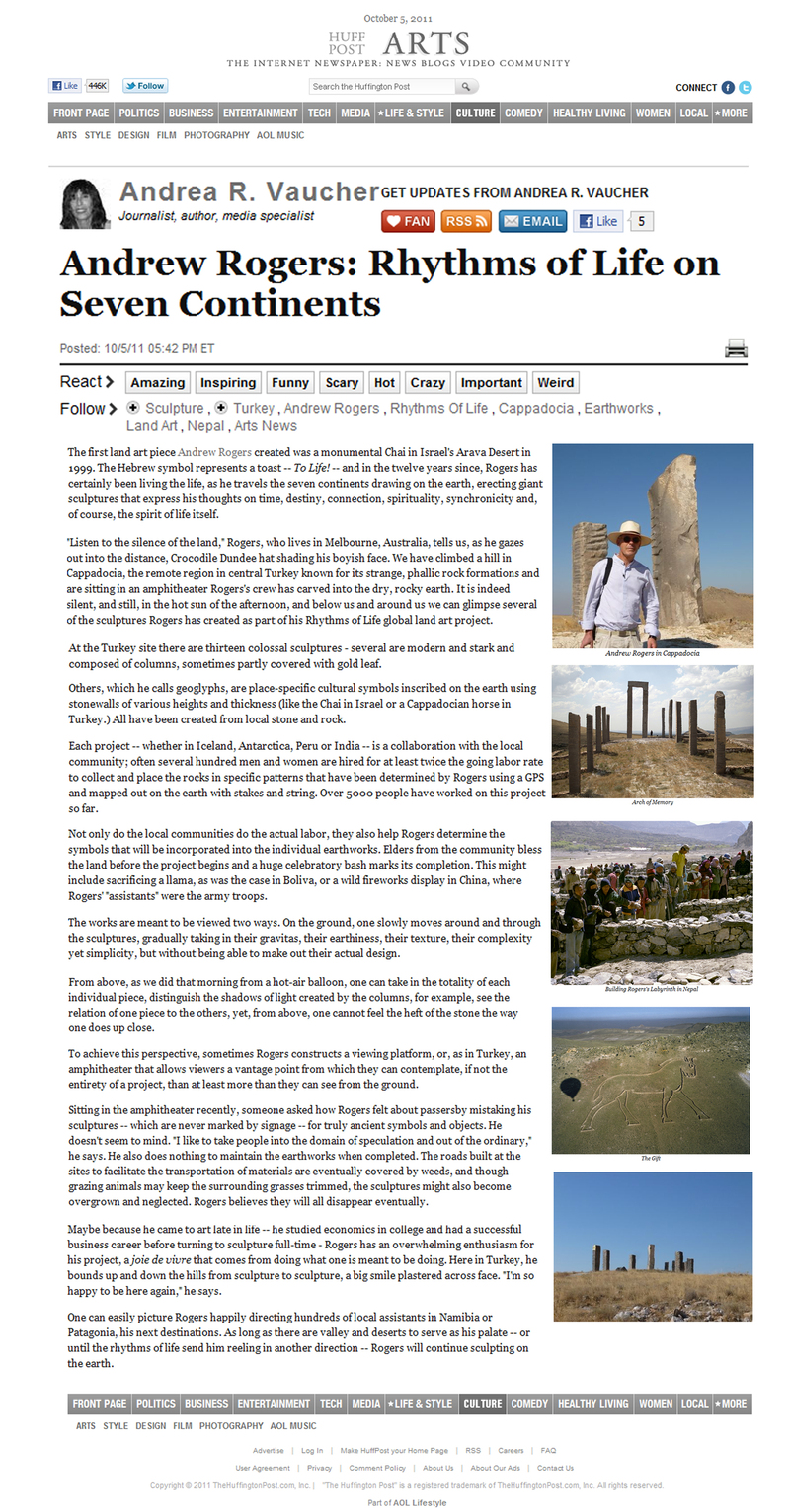

Huff Post Arts 05 October 2011

Hurriyet Daily News Spetember 2011

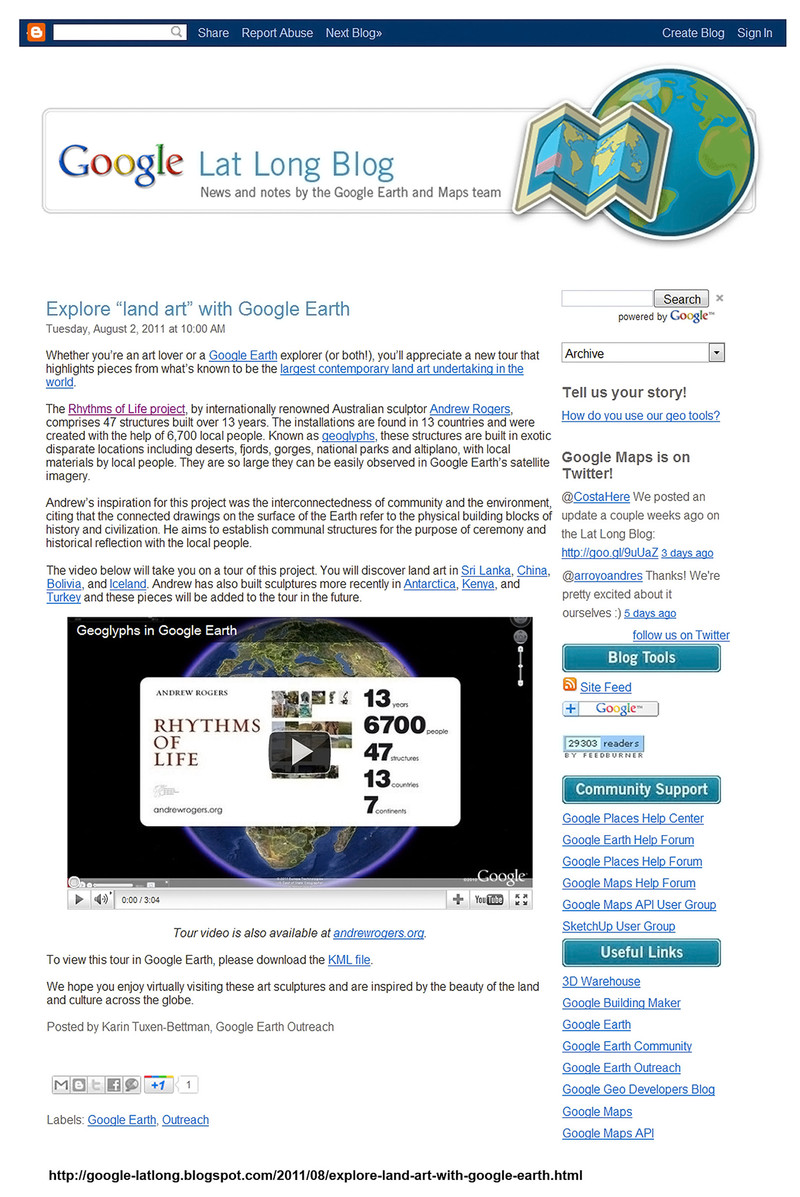

Google Lat Long Blogspot August 2011

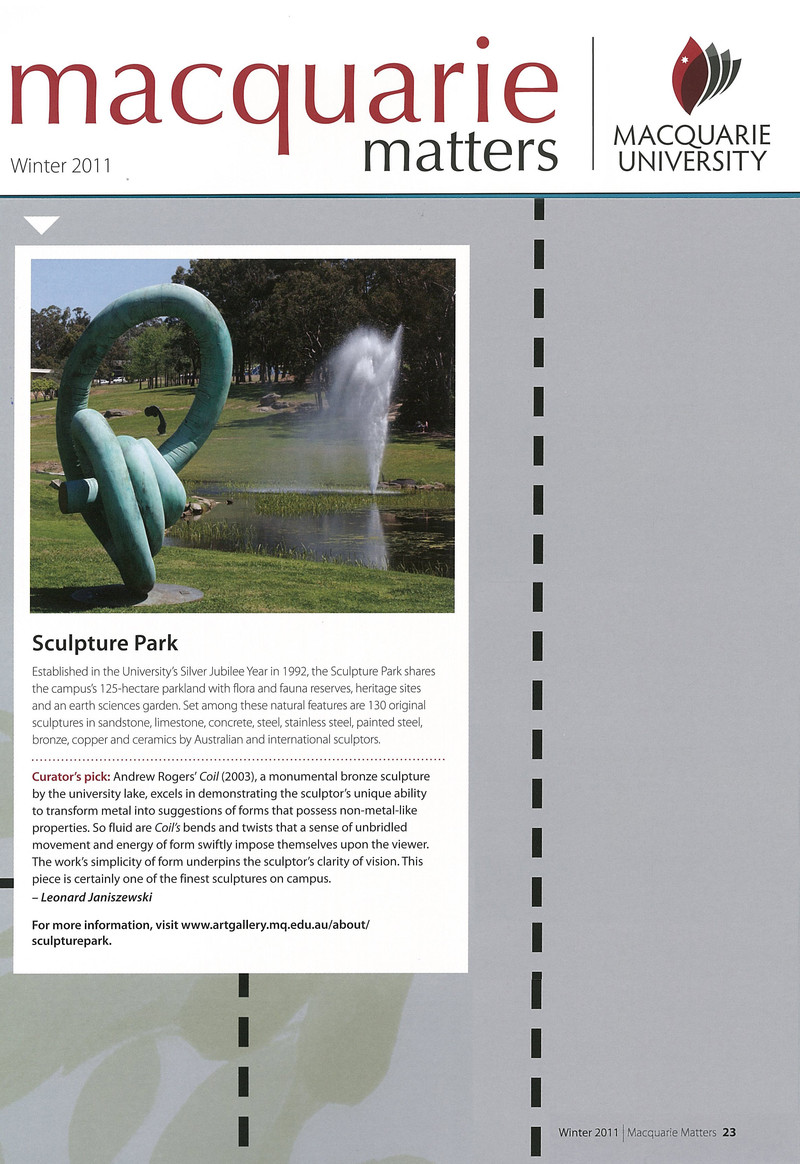

Macquarie Matters Winter 2011

The Art Newspaper May 2011

Sculpture Dec 2009

Art in America Oct 2009

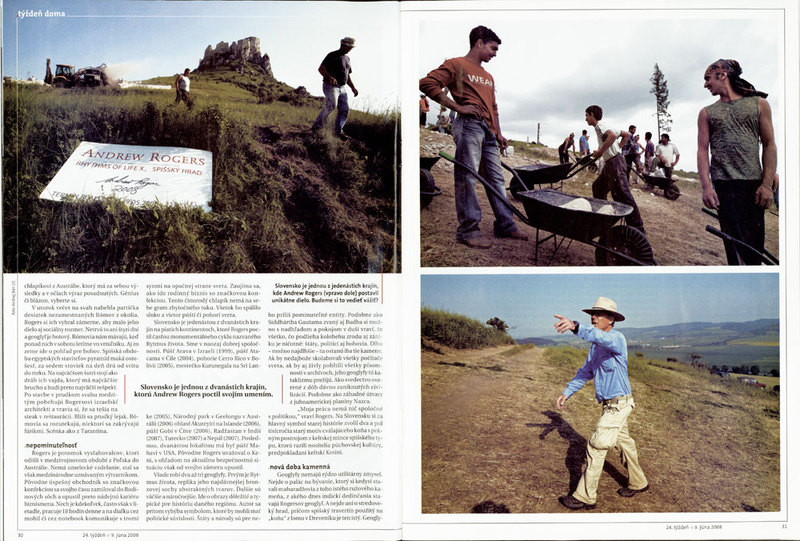

Slovakia Magazine 2008

Balanced

Balanced 1999

Hall Office Park, Texas, USA

Silicon Bronze

4.0 H x 4.5 W x 2.6 D m (13.1 x 14.8 x 8.5′)

Balanced 1999

Geelong Gallery, Victoria, Australia

Silicon Bronze

32 H x 31 W x 21 D cm (12.6 x 12.2 x 8.3″)

Living

1999

Dallas, Texas, USA

Silicon Bronze

H 4.3m

Living 1999

National Gallery of Australia, Australian Capital Territory, Australia

Silicon Bronze

41 H x 23 W x 19 D cm (16.1 x 9.1 x 7.5″)

Propagating

Propagating 1999

Montalto Vineyard, Mornington Peninsula, Victoria, Australia & Dallas, Texas, USA

Silicon Bronze

4.3 H x 2.4 W x 1.5 D m (14.1 x 7.9 x 5′)

Organic

Organic 1999

McClelland Sculpture Park+Gallery, Langwarrin, Victoria, Australia

Silicon Bronze

4.2 H x 2.2 W x 2.0 D m (13.8 x 7.2 x 6.6′)

Organic 1999

Hall Office Park, Texas, USA

Silicon Bronze

4.2 H x 2.2 W x 2.0 D m (13.8 x 7.2 x 6.6′)

Organic 1999

Deakin University, Victoria, Australia

Silicon Bronze

38 H x 21 W x 16 D cm (15 x 8.3 x 6.3″)

Ripening

Ripening, 1999

Hall Office Park, Texas, USA

Silicon Bronze

4.0 H x 3.0 W x 2.5 D m (13.1 x 9.8 x 8.2′)

Ripening 1999

Geelong Gallery, Victoria, Australia

Silicon Bronze

39 H x 28 W x 25 D cm (15.4 x 11 x 9.8″)

Becoming

Becoming 1999

Deakin University, Victoria, Australia

Silicon Bronze

41 H x 23 W x 21 D cm (16.1 x 9.1 x 8.3″)

Labile

Labile 2005

McClelland Sculpture Park+Gallery, Langwarrin, Victoria, Australia

Bronze

3.5 H x 1.5 W x 1.0 D m (11.5 x 4.9 x 3.3′)

Labile 2014

Guy Laliberte/Cirque du Soleil Collection, Quebec, Canada

Bronze

297 H x 218 W x 72 D cm (9.7 x 7.2 x 2.4′)

Labile 2005

Macquarie University, New South Wales, Australia

Bronze

3.5 H x 1.5 W x 1.0 D m (11.5 x 4.9 x 3.3′)

Surge

2004

Bronze

H 45cm

Hi Desert Star, October 2008

Mezonin, October 2008

Sabah Cuma 2007

The Australian 2006

“… I was also impressed by Andrew Rogers’s Wave, 2005,

an unwieldy but strangely commanding form of crumpled and striated bronze.”

Sebastian Smee, The Australian. December 17, 2005.

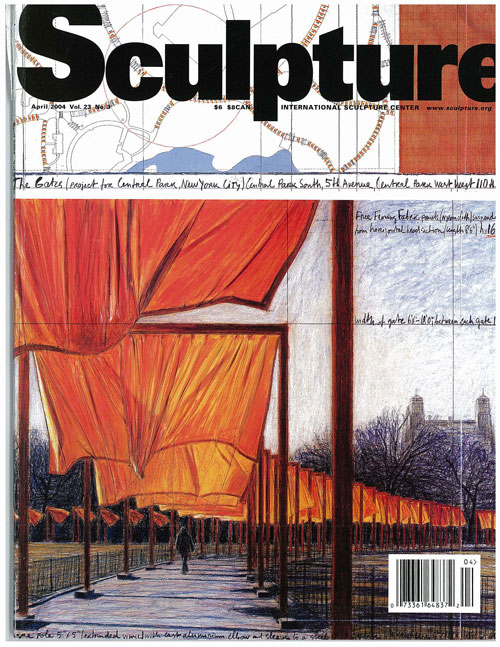

Sculpture April 2004

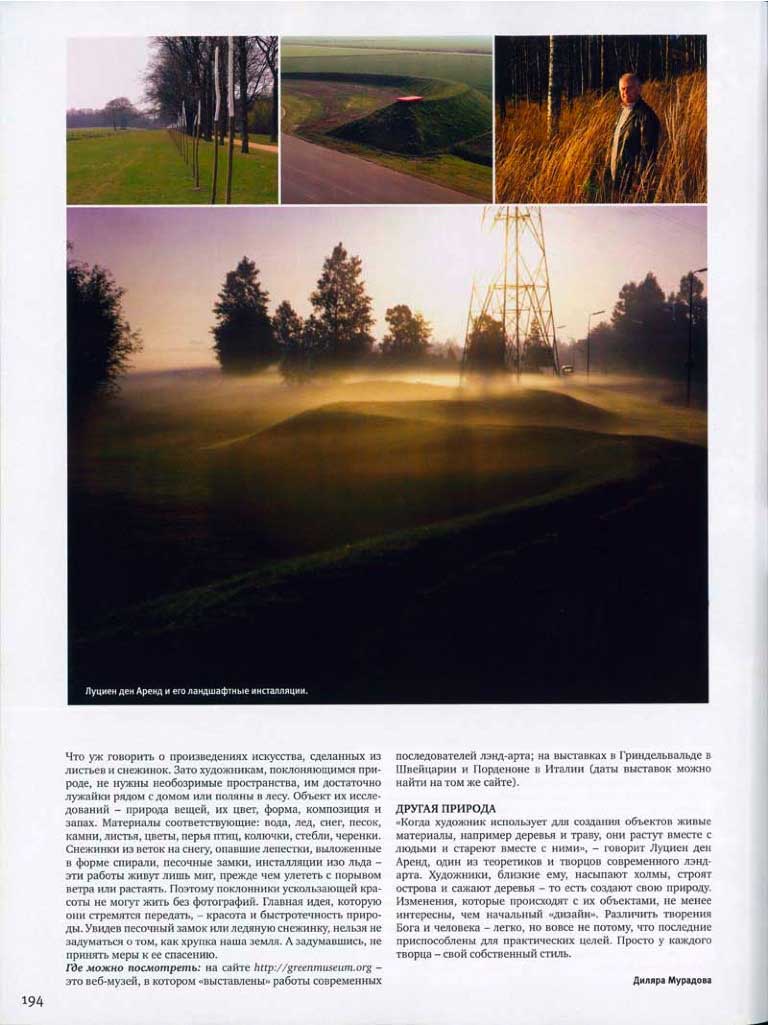

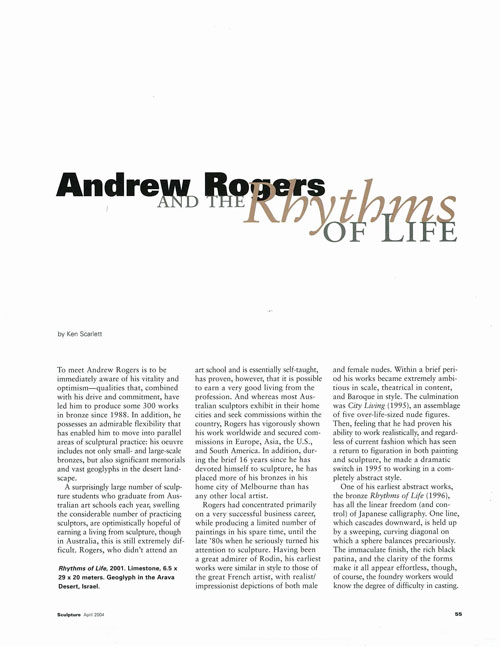

Andrew Rogers and the Rhythms of Life

By Ken Scarlett

To meet Andrew Rogers is to be immediately aware of his vitality and optimism-qualities that, combined with his drive and commitment, have led him to produce some 300 works in bronze since 1988. In addition, he possesses an admirable flexibility that has enabled him to move into parallel areas of sculptural practice: his oeuvre includes not only small- and large-scale bronzes, but also significant memorials and vast geoglyphs in the desert landscape.

A surprisingly large number of sculpture students who graduate from Australian art schools each year, swelling the considerable number of practicing sculptors, are optimistically hopeful of earning a living from sculpture, though in Australia, this is still extremely difficult. Rogers, who didn’t attend an art school and is essentially self-taught, has proven, however, that it is possible to earn a very good living from the profession. And whereas most Australian sculptors exhibit in their home cities and seek commissions within the country, Rogers has vigorously shown his work worldwide and secured commissions in Europe, Asia, the U.S., and South America. In addition, during the brief 16 years since he has devoted himself to sculpture, he has placed more of his bronzes in his home city of Melbourne than has any other local artist.

Rogers had concentrated primarily on a very successful business career, while producing a limited number of paintings in his spare time, until the late ’80s when he seriously turned his attention to sculpture. Having been a great admirer of Rodin, his earliest works were similar in style to those of the great French artist, with realist/impressionist depictions of both male and female nudes. Within a brief period his works became extremely ambitious in scale, theatrical in content, and Baroque in style. The culmination was City Living (1995), an assemblage of five over-life-sized nude figures. Then, feeling that he had proven his ability to work realistically, and regardless of current fashion which has seen a return to figuration in both painting and sculpture, he made a dramatic switch in 1995 to working in a completely abstract style.

One of his earliest abstract works, the bronze Rhythms of Life (1996), has all the linear freedom (and control) of Japanese calligraphy. One line, which cascades downward, is held up by a sweeping, curving diagonal on which a sphere balances precariously. The immaculate finish, the rich black patina, and the clarity of the forms make it all appear effortless, though, of course, the foundry workers would know the degree of difficulty in casting.

It is an elegant, joyous work. It is also traditional in that it is a single sculptural object sitting on a plinth; yet interestingly, three years later, it was to form the basis of a vast environmental work that explored new territory.

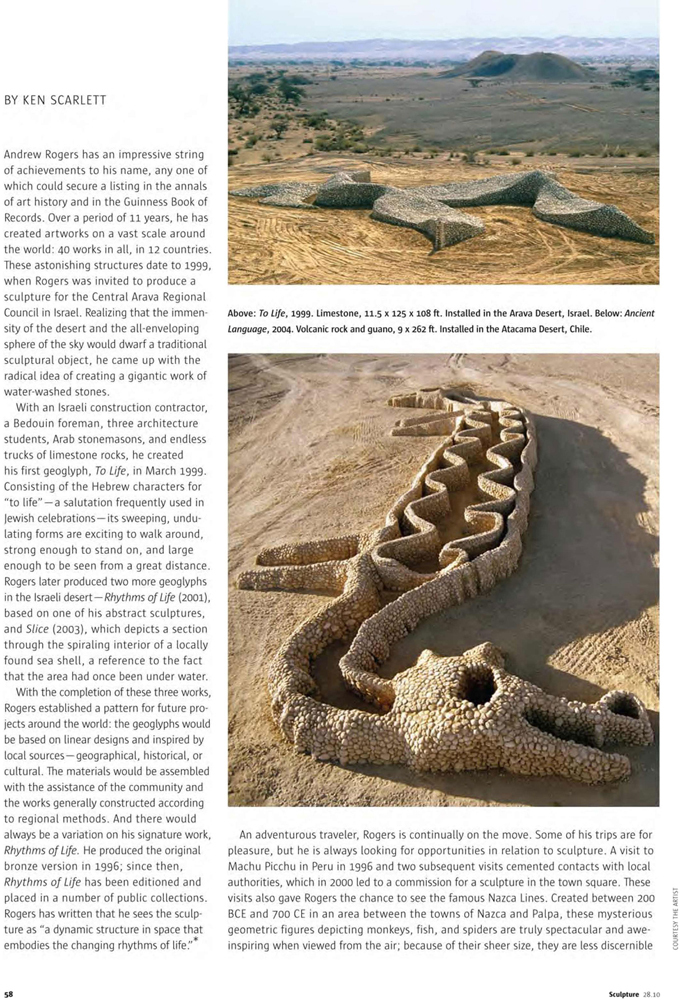

While Rogers was artist-in-residence at the Technion Institute of Technology in Haifa, Israel, in 1998, the possibility of a work in the nearby Arava Desert was first discussed. On checking the site, Rogers was immediately aware that in order to cope with the vastness of the desert, the arid, treeless hills, and the all-encompassing dome of the sky, the sculpture needed to be a huge environmental work. He returned to the desert the following year and, with the help of an Israeli construction contractor, a Bedouin foreman, many Arab stonemasons, three architecture students, innumerable truckloads of water-washed stones, and a bulldozer, supervised the construction of his first geoglyph. At 4.5 meters high, 38 meters wide, and 38 meters long, it was far larger and more ambitious than anything he had previously attempted. The motif of this work, Chai, was both strikingly simple and appropriate; it was based on two letters from the Torah, the Hebrew characters for life. “To life” is a salutation frequently used to celebrate events in Jewish life, so its symbolism was immediately appreciated and understood by the local population.

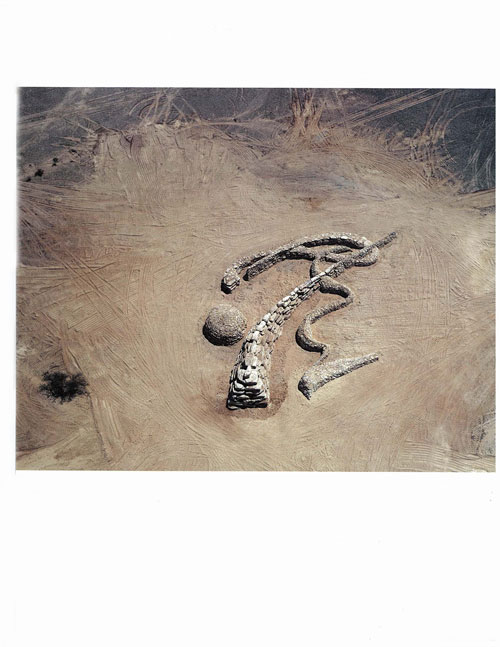

Chai was so successful that in 2001 Rogers returned to an adjoining area of desert and began the construction of another equally large geoglyph, this time based on his early abstract sculpture Rhythms of Life. The pattern was marked our in the sand with steel stakes, massive rocks that had been dynamited from the desert were brought in by the truckload, and dry stone walls were constructed then back-filled with sand until the desired forms were obtained. In the same year, the original bronze of Rhythms of Life was enlarged and installed at Southbank, outside the Concert Hall of the Arts Centre on the bank of the Yarra River, Melbourne. The locations for the two versions of this work could not be more different-one in an inhospitable desert, the other in the center of a thriving modern city. At night, one is surrounded by glittering lights and hurrying urban crowds, the other completely deserted and illuminated only by the Stars. Rogers is immensely gratified that his Rhythms of Life are meaningful to farm settlers in Israel and office workers in Australia. This, surely, is one of the reasons for his extraordinary success. His works are accessible and life-affirming, conveying a sense of optimism-a wonderful antidote when the media overwhelms us daily with news of disasters.

His Third geoglyph, Slice (2003), is literally just that-a slice through a sea shell, a fascinating and easily recognizable pattern on a gigantic scale. Again, the imagery is readily understood, as the Arava Desert was once the sea bed of an ocean.

Another early bronze, Flora Exemplar (1996), also proved to be extremely popular, and it has been issued in two larger editions, examples of which have been placed in various collections: in Vienna; in Kobe; in the Arava Desert; in the U.S. at Grounds for Sculpture, a Napa Valley vineyard, and Stonebriar Office Park; in the garden of a residential development in Melbourne; and in the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney. The director of this major Australian gallery, Edmund Capon, said of this work: “_Flora Exemplar_ is, arguably, Andrew Rogers’s most distinctive and characteristic work. In its elegant and attenuated form, which reaches up then twists and peers down, it does vaguely resemble a stem and a bud. But it is, I believe, much more than mere imitation of a natural feature, for its sheet expressiveness evokes in us emotions of human striving and introspection”.1

More recent works, while retaining the feeling of organic growth, become rougher, less obviously decorative, and more aggressive. A one-person exhibition in 2000 displayed a range of works that, while still mainly linear and retaining a sense of organic structure, are more reminiscent of geometric and mechanical forms. Living and Growth (both 1999), for instance, look as though they were assembled from industrial off-cuts, even including the pins and rods holding the various parts together. The feeling of graceful serenity that imbues many of Rogers’s earlier sculptures is frequently supplanted by short staccato forms, irregular compositions, and a more precarious sense of balance. There is also a much greater freedom in these structures, even a feeling of intuitive improvisation- Balanced (1999) is just balanced, with an extra piece pinned on top and a wedge placed under the base. And Organic (1999), in spite of its impressive size, retains the feeling of the artist’s direct involvement in twisting, folding, and compressing the original material before it was cast in bronze. Again, one has only to look at Coil (1999) to realize that Rogers also has the ability to convey his fascination with the manipulation of materials. It is very easy to envisage him in his studio exploratively tying knots with a flexible piece of rubber or styrene which, when enlarged and cast in rigid bronze, will present a visual conundrum.

These later bronzes also show a more adventurous approach to the use of color. The early works tended to be treated with a uniform patina of golden brown or lustrous black, but more recent works, particularly when enlarged, lend themselves to a range of patinas. The artist uses blue, green, brown, and even off-white to unify or, alternatively, to isolate forms. Rogers believes that his lack of formal training has given him a freedom to experiment, since he is not restricted by what is known to be possible or impossible; he certainly has presented the foundry with some challenges while achieving a very high level of craftsmanship.

In a group of small-scale works produced in 2002, Rogers experimented with the idea of combining bronze and found rocks. Leaf-like shapes are burst apart by penetrating rock; other enfolding bronzes hold rocks within their cloak-like forms; and, in some cases, thin protruding strips of bronze hold the rocks protectively. These works present a strange and unexpected combination of fragility and strength. In Mother Earth (2003), a large version of one of these curious works, the fertile earth mother is represented by the organic symbol of the leaf and the rocks appear as her progeny. One large rock (now cast in bronze) is clutched protectively to her body, while smaller rocks appear to be growing within the skin of the leaf.

In contradiction to the general elegance of his sculpture, these and some other works have an underlying Surrealist quality. Growing (1996), in spite of its obviously organic title and lily-like shape, can also be read as a strange detached ear, a listening device not only sensitive to sound bur also visually watchful.

Essentially Rogers wishes to establish a positive and open relationship with viewers, but if the occasion demands he is willing to confront them with unpalatable facts. His very moving Pillars of Witness (1999) for the facade of the Holocaust Research Centre in Melbourne is a combination of documentary panels realistically depicting the horrors of the Nazi concentration camps and symbolic pillars representing the imprisonment of Jews and the eventual birth of the new Jewish nation. Likewise, his Buchenwald Memorial (2000) is a disturbing structure, “a fractured, floating, falling form-a contrast to the perpendicular, solidly embedded gravestones that surround it.”2 It reads as a massive brick chimney, while the incised shapes on the sides appear as smoke from the incinerators of Auschwitz.

Rogers has frequently used the phrase “rhythms of life”-it serves as the title of several sculptures, the title of two exhibitions, and the title of a recently published book. It is an apt choice, for his work encompasses life and death, growth and destruction, love and hate. In this age of globalization, the rhythms of life are no longer limited to our own small circle of friends and relatives, no longer restricted to our own town or country- we are all part of a complex global pattern.

Since the first convict settlement in Sydney in ’1788, Australians have been very much aware of the tyranny of distance. In the 19th century, sailing ships rook three months to arrive from Europe; by the 1950s, the trip by sea was still six long weeks; and even now Europe is a boring 24 hours flying time away, and New York 22 hours. Australian sculptors in particular have suffered because of the distance and the cost of transporting their work to exhibition centers in Europe and America. In most cases they are not known outside Australia or even outside their home cities. It is noteworthy, then, that Rogers has broken this pattern of isolation and is helping to make Australian sculpture known throughout the world.

At the time of writing he was finalizing an agreement to construct a huge geoglyph in the Atacama Desert in Chile, based on the outline of a rock petroglyph found in the desert. This is one of the driest areas in the world (it hasn’t rained for 200 years), and the ancient rock carving has survived since approximately 800 BCE. As he has done in the Arava Desert, Rogers will build a stone structure related to the environment and capable of surviving the harshness of the weather. His work will be known in yet another country outside Australia.

Ken Scarlett’s extensive writing on contemporary sculpture includes the book Australian Sculptors.

1 Edmund Capon. “Andrew Rogers Flora exemplar,” in Rhythms of Life The Art of Andrew Rogers (Melbourne Macmillan. 2003). P. 49.

2 Andrew Rogers, 26 November 2000. quoted in ibid. p 210

|  |

|  |

|

Tour Images

A gallery of photographs of the ‘Rhythms of Life’ land art project: 48 stone structures in 13 countries and 7 continents involving over 6,700 people over 14 years

Flow 1

Flow 1 2000

Bronze

36 H x 23 W x 23 D cm (14.2 x 9.1 x 9.1″)

Ascend

2000

Bronze

36 H x 35 W x 23 D cm (14″ × 14″ × 9″)

Mount

Mount 2000

Deakin University, Victoria, Australia

Bronze and Ceramic

47 H x 45 W x 44 D cm (19 x 17.7 x 17.3″)

Climb 1

Climb 1 2000

Bronze

38h x 23w x 23d cm (15 x 9 x 9″)

Energy

1999

Silicon Bronze

H 40cm

Rhythms of Life Fire

Babi-Yar Memorial

2006

Springvale, Victoria, Australia

Bronze

Google Earth

Open this file in Google Earth to view a tour of the Geoglyphs around the world.

This Google Earth Tour was created with the assistance of Google Earth Outreach

To view in HD, start the movie and increase the resolution by clicking on the pop up menu in the bottom right hand corner and select 1080p HD.

There will be a short delay before the video recommences.

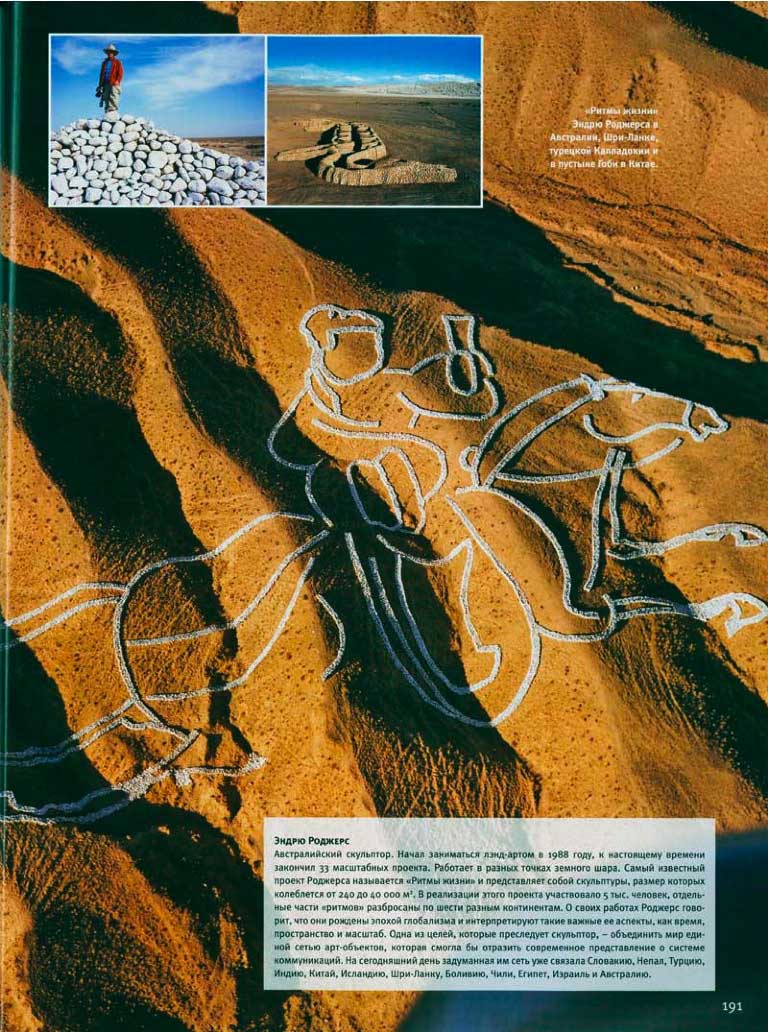

Rhythms of Life

Rhythms of Life

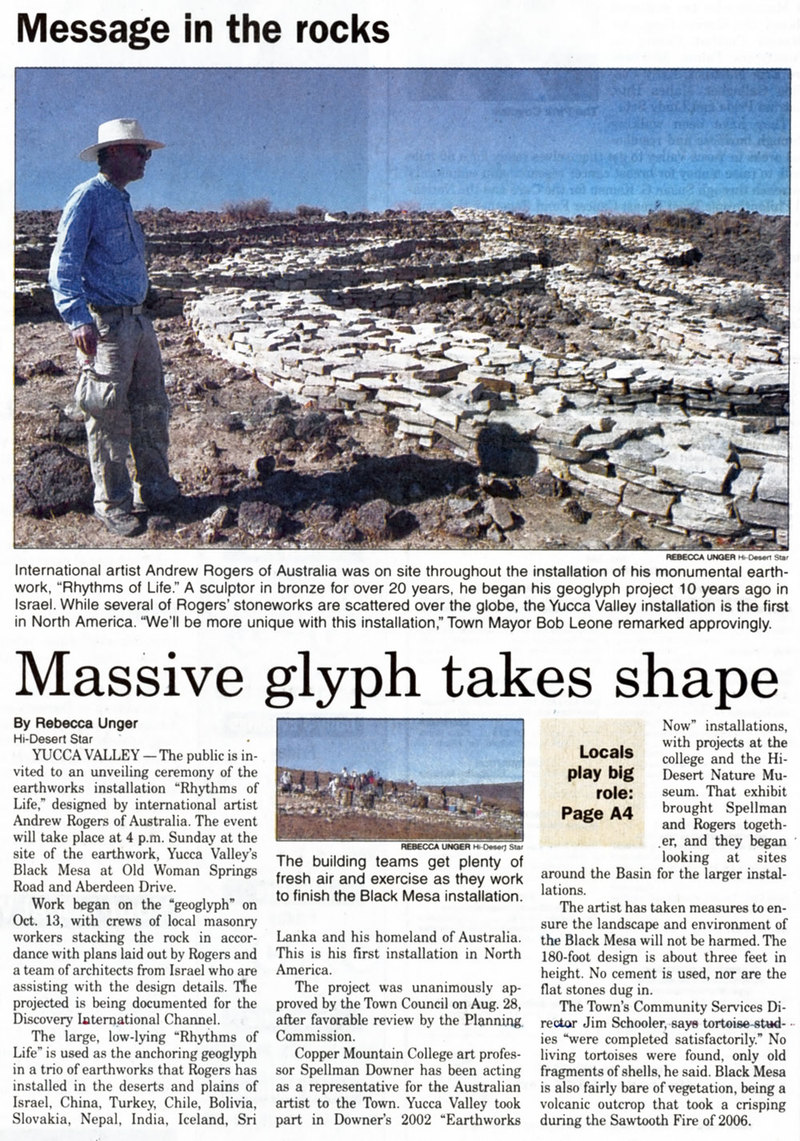

Andrew Rogers created 2 geoglyphs, ‘Rhythms of Life’ and ‘Atlatl’ on the Black Mesa in Yucca Valley near the Joshua Tree National Park.

2008

Yucca Valley

50m x 50m (164′ x 164′)

34° 11’ 09.59” N

116° 26’ 15.61” W

Atlatl

Atlatl

Andrew Rogers created 2 geoglyphs, ‘Atlatl’ (spear thrower) and ‘Rhythms of Life’ on the Black Mesa in Yucca Valley, Mohave Desert, California, USA. Artist.

2008

Yucca Valley

61m long (200′)

34° 11’ 11.57” N

116° 26’ 16.20” W

Tomb

2005

Melbourne, Australia

Bronze

Ratio Utah

Ratio, Utah

In response to a request to realise a gentleman’s dream, Andrew Rogers created ‘Ratio’ in Green River Utah. It is based on the Fibonacci Sequence.

2010

Green River, Utah

13.5m H x 13m W x 2m D (44′ × 42′ × 6′)

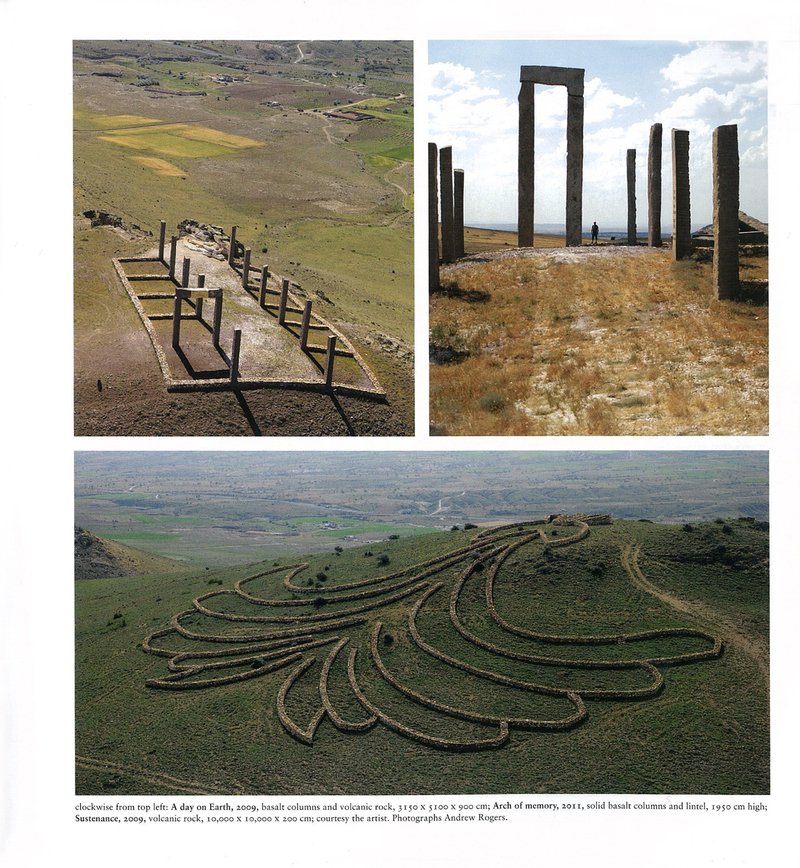

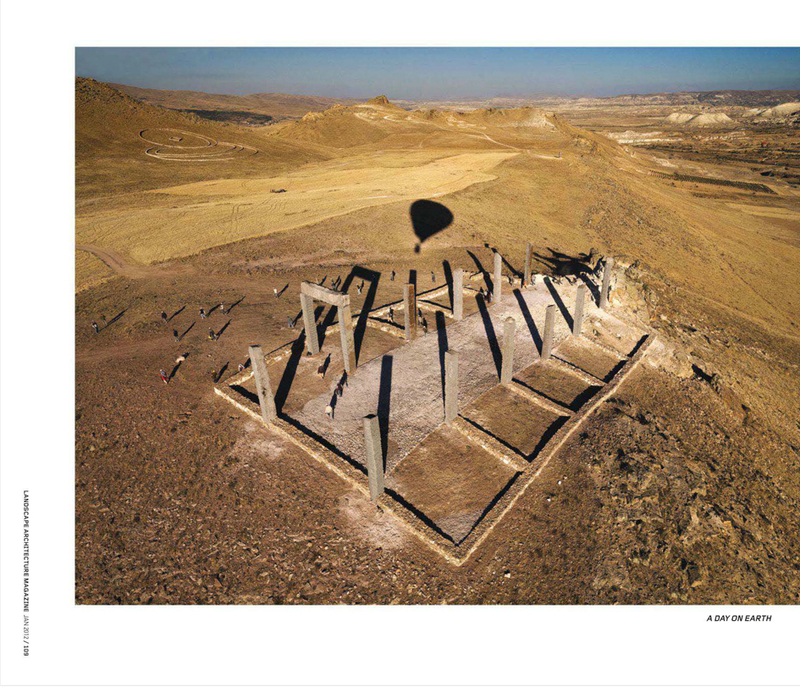

A Day on Earth

A Day on Earth

A Day On Earth is the largest of Andrew Rogers’ stone structures in the ‘Time and Space’ land art park in Cappadocia Turkey.

Completed in 2009, it measures 31.5m x 51m x 19.5m.

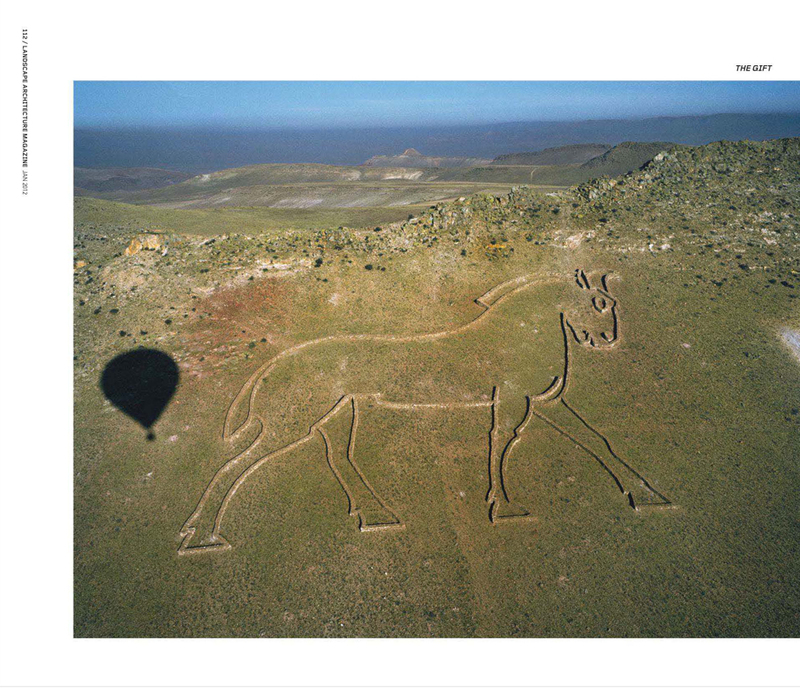

The Gift

The Gift

Andrew Rogers’ geoglyph ‘The Gift’ derives from a 6000 year old rock carving and signifies the important role horses played in Cappadocia in ancient time.

Completed in 2007, it measures 60m x 60m.

34 deg 46’ 40.458 deg E

38 deg 41’ 4.634 deg N

Buchenwald Memorial

2000

Springvale, Victoria, Australia

Bronze

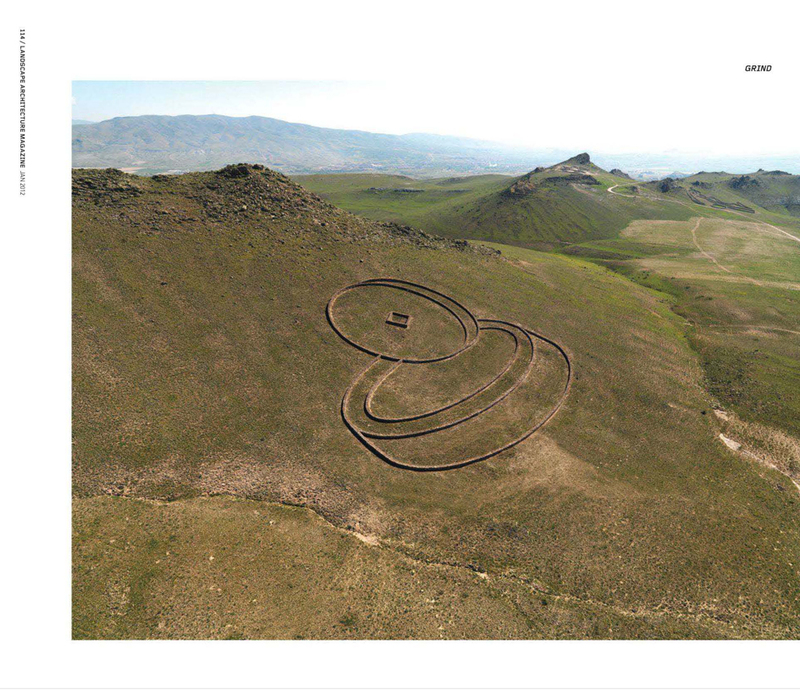

Grind

Grind

Andrew Rogers’ geoglyph ‘Grind’ is derived from an ancient millstone that belonged to the elders of the town of Goreme in Cappadocia.

Completed in 2009, it measures 100m x 100m.

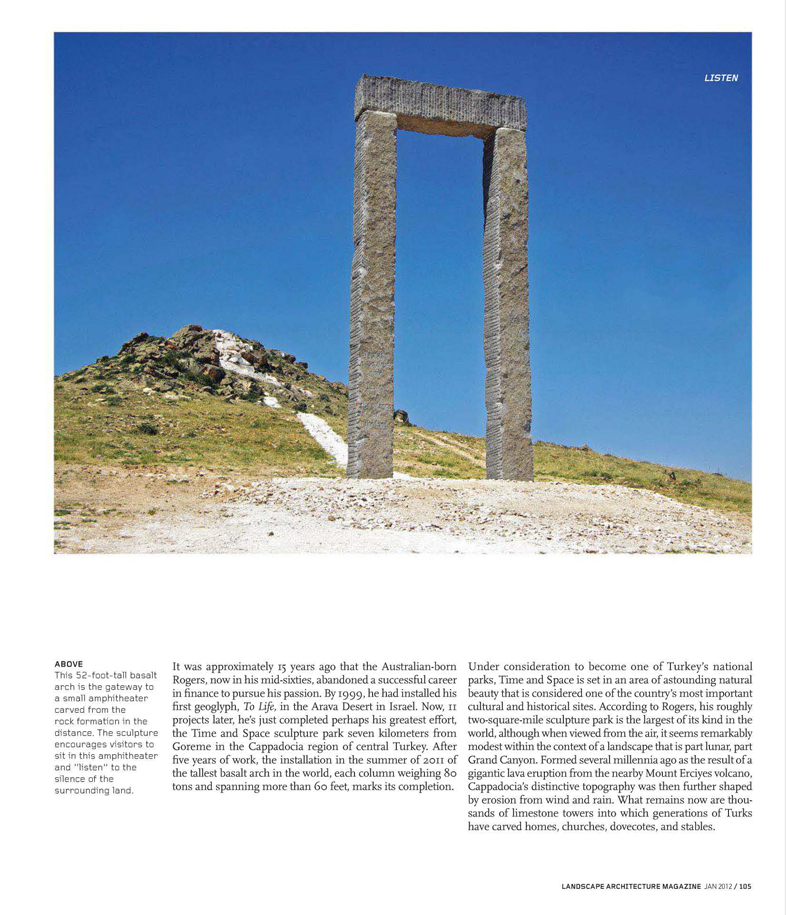

Listen

Listen

‘Listen’; a 52ft high arch and carved amphitheatre created by Andrew Rogers at the ‘Time and Space’ land art park in Cappadocia, Turkey.

Carved from the natural rock, it was completed in 2010.

Fire & Understanding, Linzhou, China

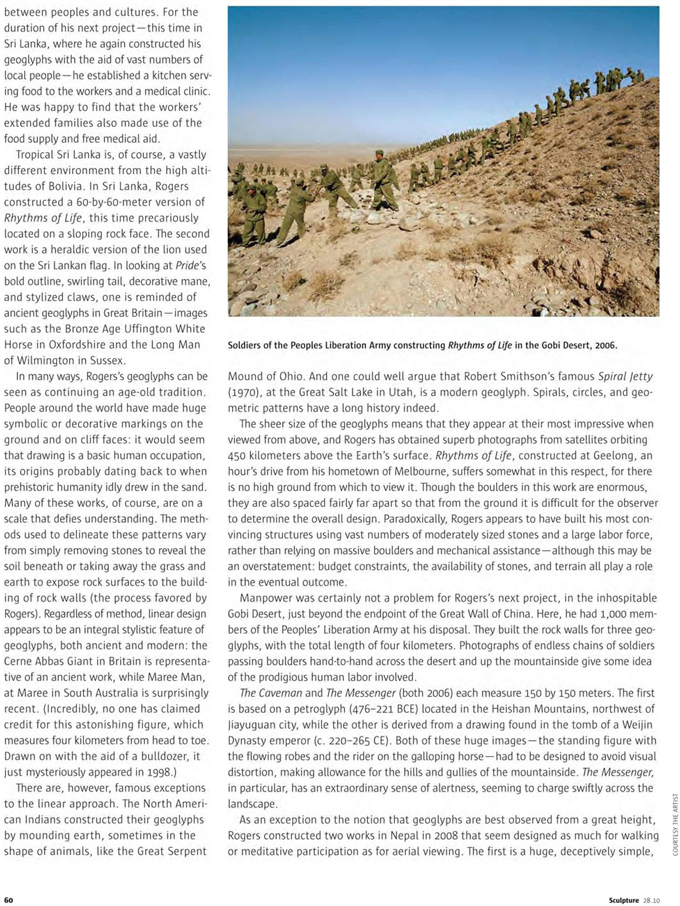

‘Dragon’ – 4,000 people

Taihang Great Valley, Linzhou, China

Length of outline – 814m (2,670’)

‘Fibonacci Sequence’ – 3,500 people

Red Flag Canal, Linzhou, China

74.25m x 76.50m (244′ × 251′)

Time and Space

Time and Space

Andrew Rogers’ spectacular Fibonacci sequence of 12 basalt pillars. The sequence is demonstrated both in terms of height and spacing.

Completed in 2009, measuring 24m x 16m x 5.3m.

Cappadocia.

Predicting the Past

Predicting the Past

2009

Cappadocia

4.2m x 4.7m x 1.1m (14’ x 15.5’ x 3.6′)

“The arch is about not projecting another yesterday and it is about the difference between the past and the future. What will be the future?”

Rhythms of Life

Rhythms of Life

Rhythms of Life by Andrew Rogers embodies the changing rhythms of life reflected in the juxtaposition of shape & line echoing life’s unpredictable journey.

2007

Cappadocia

100m x 90m

34 deg 47’ 53.456E

38 deg 41’ 36.276N

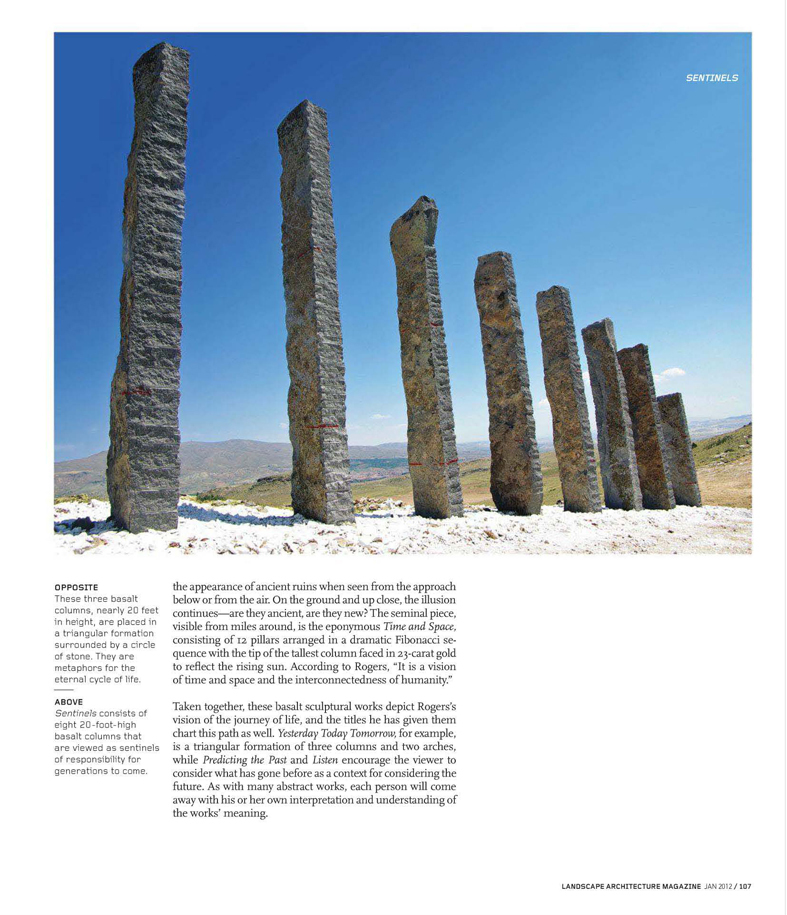

Sentinels

Sentinels

Sentinels of responsibility for generations to come. Located in the’Time & Space’ land art park, Cappadocia Turkey.

2010

8 basalt columns

6m in height (approximately) (19.7ft)

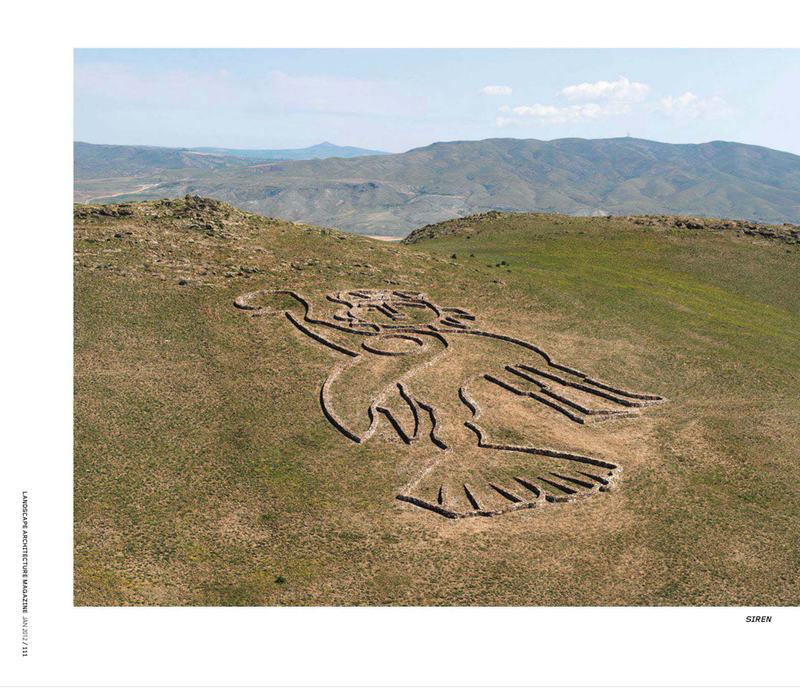

Siren

Siren

Siren by Andrew Rogers. Human head and body of a bird – in shamanistic beliefs they accompany humans in their journeys to the underworld and the heavens.

2009

Cappadocia

65m x100m (213’ x 328’)

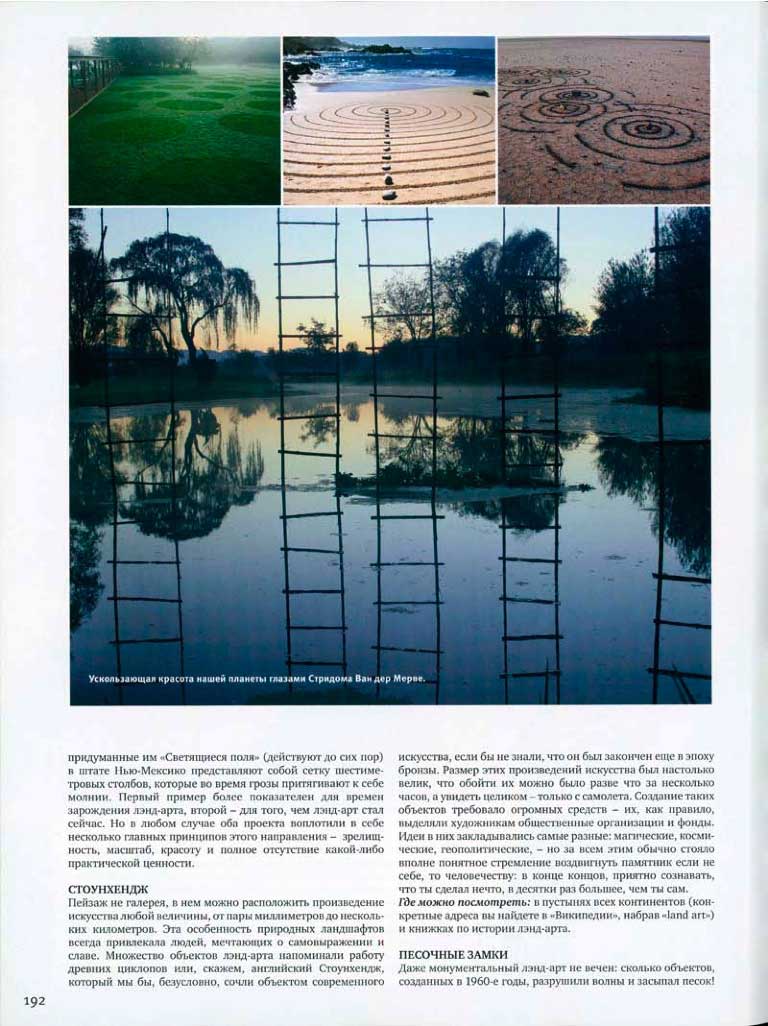

Winding Path, Basel, Switzerland

Basel, Switzerland

12 June 2012

An ephemeral installation created with the citizens of Basel during Art Basel.

22m x 21m (72′ × 69′)

Strength

Strength

‘Strength’, ‘Time & Space’ land art park, Cappadocia by Andrew Rogers. A double bodied lion derived from an image found in the Sultanhanı Township, Aksaray.

2009

Cappadocia

100m x 50m (328’ x 165’)

Total length of walls 830m (2,723 ft)

Soar

Soar 2003

Bronze

40h x 19w cm (16 x 8″)

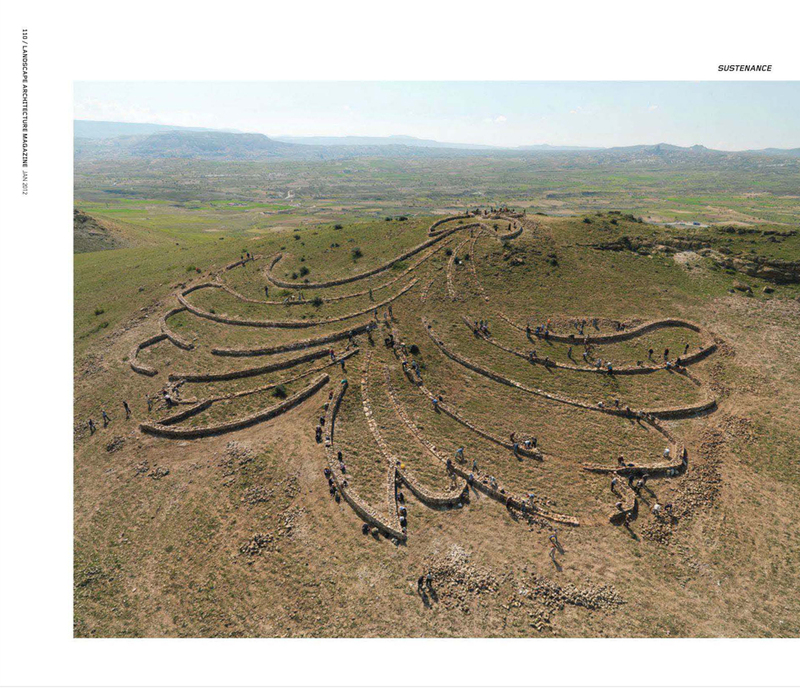

Sustenance

Sustenance

Sustenance by Andrew Rogers Cappadocia Turkey. The date palm motif is found on a royal tomb built in the thirteenth century on the Kayseri Talas road.

2009

Cappadocia

100m x 100m (328ft x 328ft)

Total length of walls 897m (2,942ft)

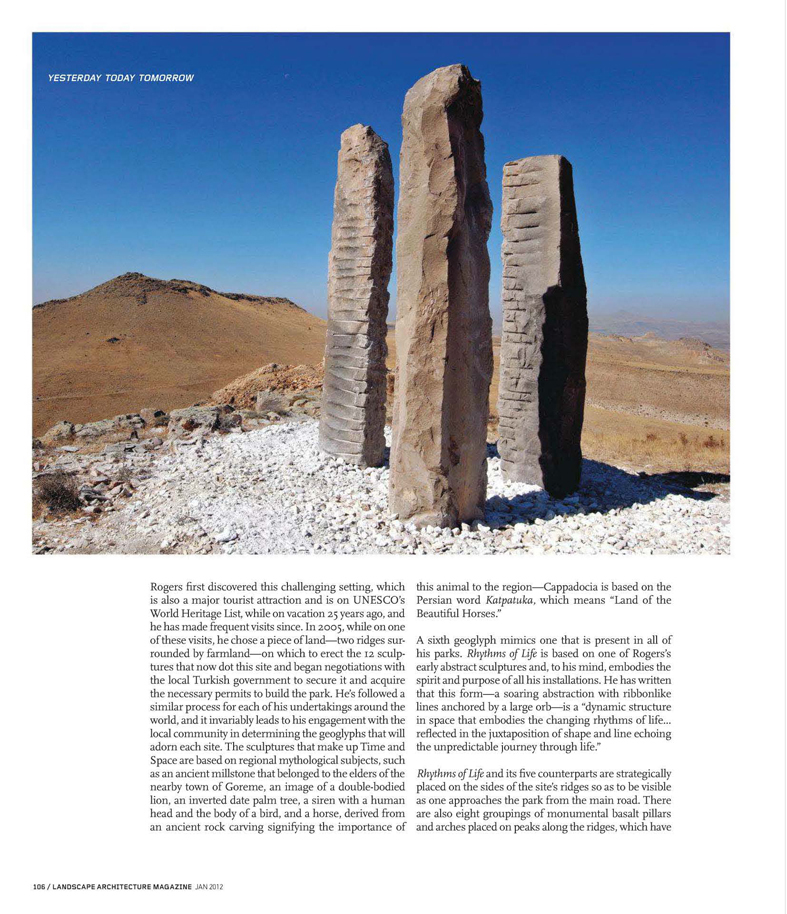

Yesterday Today Tomorrow

Yesterday Today Tomorrow

Yesterday Today Tomorrow by Andrew Rogers, Cappadocia Turkey. “Life goes on …” A triangular formation surrounded by a circle of stone.

2009

Cappadocia

Three basalt columns

6m (19.7ft) high

Rise

Rise 2000

Bronze

4.5 H x 4.0 W x 2.0 D m (14.8 x 13.1 x 6.6′)

Rise 2000

National Gallery of Australia, Australian Capital Territory, Australia

Bronze

44 H x 38.8 W x 24 D cm (17.3 x 15.3 x 9.4″)

Presence

Presence

‘Presence’ by Andrew Rogers comprises 24 basalt columns and is located at the 2.5km long ‘Time & Space’ land art park in Cappadocia, Turkey. Sculpture

2011

Cappadocia

24 basalt columns

up to 9m (30ft) high

38 × 22 × 9m

(125′ × 72′ × 30′)

Rhythms of Life

Rhythms of Life

In 2005, Andrew Rogers created geoglyphs ‘Rhythms of Life’ and ‘Pride” and the stone structure ‘Ascend’ in Kurunegala, Sri Lanka.

Rhythms of Life measures 60m x 60m, and was placed on the steepest site in the area.

7 deg 29’ 30.56 deg N

80 deg 21’ 34.89 deg E

Ascend

Ascend

In 2005, Andrew Rogers created ‘Ascend’ a 6.5m high stepped stone structure in Kurunegala, Sri Lanka. The steps of Ascend are based on the Fibonnaci Sequence.

Ascend consists of a staircase with steps that increase in size exponentially according to the Fibonacci number series.

To create this work, workers formed a human chain, passing rocks along an extremely steep rock slope to reach the site.

It is made of granite and measures 6.5m long x 6.5m high.

3 deg 59’ 03.87 deg N

84 deg 58’ 11.94 deg E

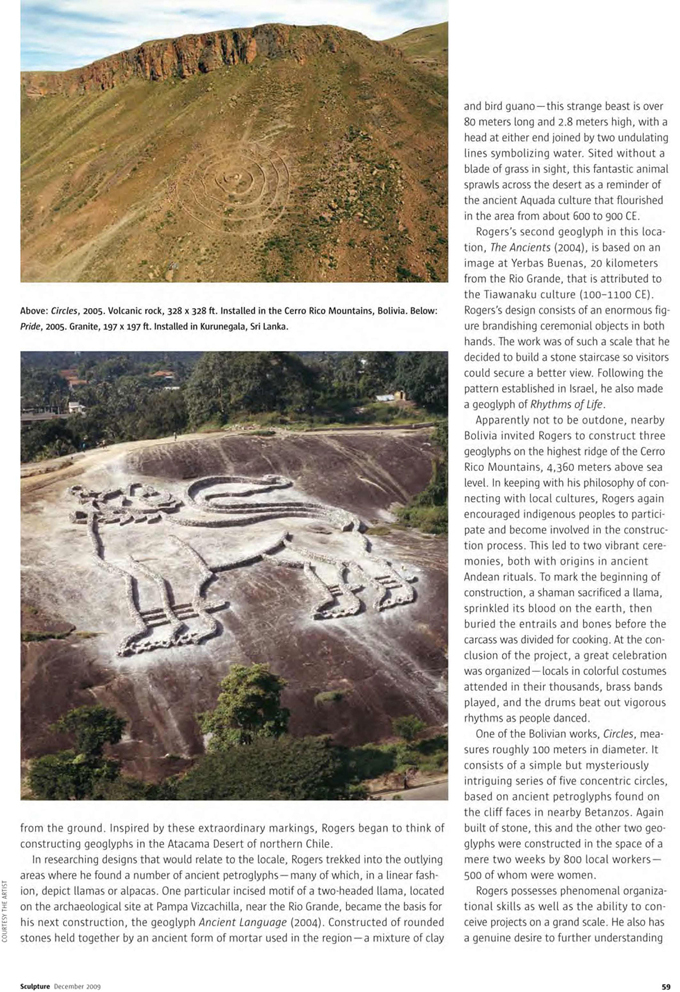

Pride

Pride

In 2005, Andrew Rogers created the geoglyph ‘Pride’, a stylised lion, at the Rhythms of Life project site in Kurunegala, Sri Lanka.

Measuring 60m x 60m, the lion is outlined with thick granite stone walls and bears the regal stance of its symbolic predecessors. Its head os represented in profile, while its body is turned so that all four legs are lined up with abstract symmetry.

This geoglyph is also locate on a sheer rock face that slopes down toward the lake below.

7 deg 29’ 32.35 deg N

80 deg 21’ 34.26 deg E

Rhythms of Life

Rhythms of Life

In the High Tatras of Slovakia Andrew Rogers created the Rhythms of Life geoglyph in local granite.

2008

High Tatras

35m x 45m

Granite

49° 08’ 29.38” N

20° 13’ 52.26” E

Escalate

Escalate 2000

Deakin University, Victoria, Australia

Bronze

33 H x 19 W x 16 D cm (13 x 7.5 x 6.3″)

Sacred

Sacred

Andrew Rogers created ‘Sacred’ with white travertine marble near ancient Spissky Castle in Slovakia. ‘Rhythms of Life’ was created on the High Tatras.

2008

Poprad

100m x 100m

Travertine Marble

49° 00’ 10.28” N

20° 46’ 13.82” E

Rhythms of Life

Rhythms of Life

Andrew Rogers’ ‘Rhythms of Life’ geoglyph in Jomsom, Nepal faced a vista of pristine snowcapped mountains. Hundreds of local Nepalese assisted.

2008

Jomsom

60m x 60m (197′ x 197′)

28° 47’ 27.14” N

83°44’ 21.49” E

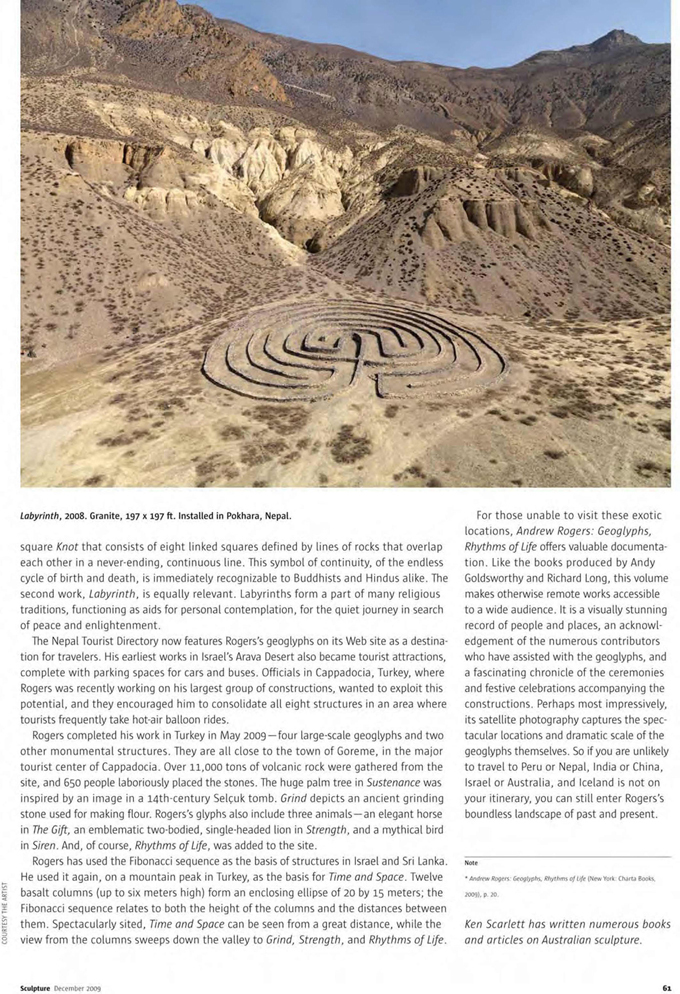

Labyrinth

Labyrinth

The first of Andrew Rogers’ Labyrinths, this ‘Winding Path’ in Jomsom, Nepal faces pristine snow capped mountains.

2008

Jomsom

100m x 100m (330′ x 330′)

28° 47’ 26.21” N

83° 44’ 15.77” E

Knot

Knot

The geoglyph ‘Knot’ was created by Andrew Rogers in Pokhara, Nepal with the assistance of hundreds of Nepalese people.

2008

Pokhara

60m x 60m (197′ x 197′)

28° 10’ 50.89” N

83° 59’ 47.55” E

Sacred Fire

Sacred Fire

Andrew Rogers worked with the Himba people of Namibia to create ‘Sacred Fire’.

2012

Namib Desert

14 m diameter (46’)

17° 14’ 04.70” S

12° 13’ 23” E

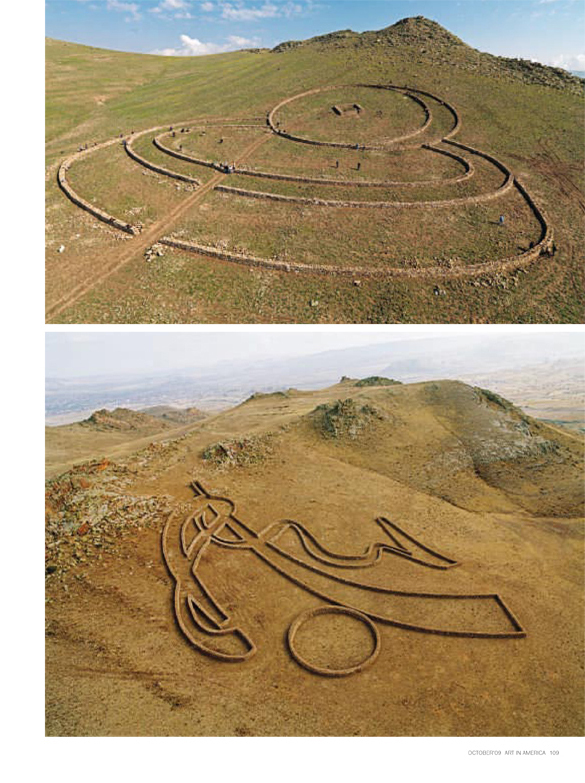

Shield

Shield

The Geoglyph ‘Shield’ created in the Chyulu Hills of Kenya with the assistance of 1,270 Maasai – the largest such gathering of Maasai in recent history.

2010

Chyulu Hills

100m x 70m x 1.5m (328′ × 230′ × 5′)

1.2km (3940’) of rock walls

2° 50’ 28.26” S

37° 54’ 35.87” E

Rhythms of Life Kenya

Rhythms of Life, Kenya

Andrew Rogers created the geoglyph ‘Rhythms of Life’ in the Chyulu Hills of Kenya with the assistance of 1,270 Maasai.

2010

Chyulu Hills

69m x 69m (226′ × 226′)

2° 50’ 27.55” S

37° 54’ 29.64” E

Lions Paw

Lions Paw

Andrew Rogers created the Geoglyph ‘Lions Paw’ in the Chyulu Hills of Kenya with the assistance of 1,270 Maasai.

2010

Chyulu Hills

40m x 40m x 2m (131′ × 131′ × 6.6′)

2° 50’ 26.52” S

37° 54’ 38.69” E

Celebration of Life

In 2006, 42 beautifully pregnant women were photographed by Andrew Rogers on his geoglyphs ‘To Life’ (Chai) and ‘Rhythms of Life’ in the Arava Desert, Israel.

To Life

To Life (Chai)

In Israel, the Rhythms of Life site stretches over one square kilometre near ancient Nabatean ruins and a spice route from antiquity.

‘To Life’ was the first geoglyph created by Australian artist Andrew Rogers. Based on the Hebrew word “Chai’ it is located in the Arava Desert in Israel.

To Life (Chai) was completed in 1999, measuring 38m x 33m (125′ x 108′).

30° 36’17.78” N

35° 11’46.96” E

Mother Earth 5

2002

Melbourne, Australia

Bronze & Stone

50 H x 15 W x 25 D cm (20″ × 6″ × 10″)

Rhythms of Life

Rhythms of Life

Andrew Rogers created the first ‘Rhythms of Life’ geoglyph in the Arava Desert, Israel in April 2001. It measures 29m x 24m.

The Rhythms of Life site stretches over one square kilometre near ancient Nabatean ruins and a spice route from antiquity.

30° 36’39.23” N

35° 12’20.57″ E

Slice

Slice

‘Slice’ (2003) is a cross section of a sea shell, and a reminder the Arava Desert was once a sea bed brimming with life. It measures 80m x 38m.

The Rhythms of Life site stretches over one square kilometre near ancient Nabatean ruins and a spice route from antiquity.

30° 36’17.69” N

35° 11’39.43″ E

Mother Earth 4

2002

Melbourne, Australia

Bronze & Stone

55 H x 26 W x 24 D cm (22″ × 10″ × 10″)

Ratio

Ratio

Andrew Rogers created a pristine white structure edged in 23-carat gold to reflect the sun each morning as it rises over the Arava Desert, Israel.

The Rhythms of Life site stretches over one square kilometre near ancient Nabatean ruins and a spice route from antiquity. Ratio was completed in 2004 based on the proportions of the golden ratio. It is located on a mountaintop not far from Sapir, measuring 32m long x 8m high.