Downloadable Article: The Art Newspaper 21May12

Sculptures, satellites and what it means to be human

Artist Andrew Rogers wants to shrink the world and get us all to work together

By Elizabeth Fortescue. Web only

Published online: 21 May 2012

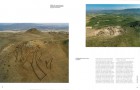

The Australian artist Andrew Rogers is due to travel to Namibia in southwest Africa in August to work alongside nomadic Himba tribespeople on a stone geoglyph or earth sculpture. The “earth drawing”, as Rogers calls it, will measure hundreds of metres across and will be photographed by satellite on completion. The Namibia project will be the next phase of Rogers’s seven-continent “Rhythms of Life” series. The series inspired Google to make a video tour of the globe in which Rogers’s geoglyphs can be seen in satellite imagery.

Rogers says he will arrive in the Namibian capital, Windhoek, on 14 August and travel to a rural, riverside location where he will “sit down and talk to [the Himba people] about what they would like to see recreated on the ground”.

“These structures will relate to [the Himba’s] history and heritage,” Rogers says.

Three structures will be created in the Namibian desert from the local stones. Rogers will offer to make one of his signature “Rhythms of Life” geoglyphs of which he has made versions on all seven continents, beginning in 1998.

It is part of his usual practice to involve local people in the creation of the works. So far he has created 48 geoglyphs in 13 countries with a total of 6,700 people, including 1,000 Chinese soldiers in the Gobi desert and 1,270 Maasai tribespeople in Kenya. Other countries with Rogers’s geoglyphs include Chile, Nepal, Bolivia, Sri Lanka, India and Australia.

Nearly all Rogers’s geoglyphs are left standing in the landscape where they will eventually disintegrate and be reclaimed by nature.

“Even though it may take a couple of hundred years to be reabsorbed into the landscape, they [eventually] will be,” Rogers says.

In March this year, Google Earth Outreach launched a video which pans around the world and zooms in on Rogers’s geoglyphs in deserts, flat lands, on prominences and mountains.

Rogers arranges for private satellite companies to photograph each of the completed geoglyphs from 880 kilometres above the surface of the earth. “It’s very humbling because you realise how large the world is and how minute these things are,” he says.

An exhibition of large-scale photographs of the Rhythms of Life earth drawings goes on display at Hammer Gallery in Zurich from 9 June. On 11 and 12 June Rogers will work with 1,000 Zurich citizens to create a labyrinth in a town square. He declines to divulge the exact location.

The walls of the labyrinth will be made from a 180 metre tube of plastic netting which Rogers’s collaborators will fill with thousands of biodegradable plastic bottles. The work, titled Another Way, will be a “tool for contemplation” about the impact of garbage on the environment, he says. The labyrinth will be up to 1.5 metres high and remain in the square for two days before being taken down and recycled. As usual, satellite photographs will be taken of the Zurich work.

Rogers says his Rhythms of Life geoglyphs were inspired by the ancient Nazca lines of Peru. Other ancient examples of this form of art, including the White Horse on Salisbury Plain in the UK, show that humans have been compelled to create geoglyphs for thousands of years.

“I think it’s probably a respect for something which is fundamental, which is our earth and the rocks and structures that form our environment,” Rogers says. “I try and rearrange what’s on the surface. We are very sympathetic. We follow the contours of the land. I suppose it’s a fascination with nature.”

Rogers said he earns nothing from his geoglyphs, which are funded by a range of sponsors. A former economist, he earns his living from his sculptural practice with studios in Melbourne and the Mornington Peninsula, Victoria. Rogers’s 7.5-metre bronze sculpture of a female nude, titled Perception and Reality I, was unveiled at Canberra Airport in April.